There are a number of offensive words in Vietnamese. Some examples are:

Di chet di (go kill yourself) , cha (dad) or me (mom), do quy (evil), do ngu (stupid), do khung (mad).

This is, she informed me, merely a short list, and she could have gone on, but I did not think an exhaustive list was required.

Like in the United States, using these towards a close friend in a joking manner is often acceptable, but even then they have to be careful to ensure it isn't misconstrued. Typically, hateful speech is not directed at other groups, and is mostly used within the Vietnamese culture between individuals who dislike each other.

Hate speech is not protected speech, and is prohibited in schools, but she does not think the government has ever prosecuted anyone for using it. Rather, it's typically the family who punishes a person for using it out of an acceptable context, and generally by less educated families.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Gender Relations

Before, women were treated very poorly in Vietnam. At home, they had no voice, and were required to do whatever it was their husbands said. Nowadays, they're permitted a great deal more freedom, and if a woman happens to earn more money than her husband, she has significant authority.

There is no morphological difference in Vietnamese with respect to gender, and men and women both speak the same way grammatically and lexically. However, men do speak more quickly, loudly, and aggressively than women do, though she said this is not as prevalent as it was before women started to gain more social liberty.

As mentioned before, men do like to stand closer to one another than women do. There is no real difference in genders, the only changes are when they're directed between the sexes, where caution is expected owing to the strength of marriage obligations.

There is no morphological difference in Vietnamese with respect to gender, and men and women both speak the same way grammatically and lexically. However, men do speak more quickly, loudly, and aggressively than women do, though she said this is not as prevalent as it was before women started to gain more social liberty.

As mentioned before, men do like to stand closer to one another than women do. There is no real difference in genders, the only changes are when they're directed between the sexes, where caution is expected owing to the strength of marriage obligations.

Argument

There was very little to say on this subject, though I did my best to broaden it.

There is very little argument between different social strata. Like many Asian cultures, authority is very important, though those of a higher status (whether from age or social position) will listen to younger individuals. Between members of the same social strata, there may be arguments between people (especially older men) that seem to exist largely for entertainment or handling disputes, but she didn't have much to say on the subject. I suspected, and she confirmed, that it was a way of expressing camaraderie.

Not wanting to end with that, I broadened the subject to include political dissent, which she emphatically stated was disallowed. The only people allowed to say anything against the government are state-sponsored individuals. Before the Communists took over, this was also the case, though it was the King who had the final say instead.

Curiously, there are many religions alive in Vietnam and permitted to flourish as they will. There are also, I discovered to my surprised, numerous ethnic groups, though these cultures tend to dislike the government and it works to oppress them.

There is very little argument between different social strata. Like many Asian cultures, authority is very important, though those of a higher status (whether from age or social position) will listen to younger individuals. Between members of the same social strata, there may be arguments between people (especially older men) that seem to exist largely for entertainment or handling disputes, but she didn't have much to say on the subject. I suspected, and she confirmed, that it was a way of expressing camaraderie.

Not wanting to end with that, I broadened the subject to include political dissent, which she emphatically stated was disallowed. The only people allowed to say anything against the government are state-sponsored individuals. Before the Communists took over, this was also the case, though it was the King who had the final say instead.

Curiously, there are many religions alive in Vietnam and permitted to flourish as they will. There are also, I discovered to my surprised, numerous ethnic groups, though these cultures tend to dislike the government and it works to oppress them.

Bilingualism

There was a curious sort of dichotomy on this subject.

On the one hand, my partner noted large advantages for being bilingual. She could learn more about English culture, she could attend school here with relative ease, and she could take any number of jobs. Currently, she works as a Vietnamese localizer for a Korean advertising firm, for example. English is a very common second language in Vietnam, and is taught in their schools, as noted prior.

She has encountered no prejudice or disadvantages for being bilingual, though her native English speaking cousins often tease her about her accent.

What I found especially interesting was when she expressed her desire for everyone to learn English, potentially replacing their native tongues. She seemed to feel that if we all spoke the same language, we'd all be more connected, which can only be for the betterment of all.

I tried to ask if she thought differently when speaking in the different languages, but she seemed to have some trouble understanding what I was getting at. I think I got the point across eventually, but she only gave a vague 'not really' and didn't seem to think there was a difference. Not being able to speak Vietnamese myself, I was unable to check.

On the one hand, my partner noted large advantages for being bilingual. She could learn more about English culture, she could attend school here with relative ease, and she could take any number of jobs. Currently, she works as a Vietnamese localizer for a Korean advertising firm, for example. English is a very common second language in Vietnam, and is taught in their schools, as noted prior.

She has encountered no prejudice or disadvantages for being bilingual, though her native English speaking cousins often tease her about her accent.

What I found especially interesting was when she expressed her desire for everyone to learn English, potentially replacing their native tongues. She seemed to feel that if we all spoke the same language, we'd all be more connected, which can only be for the betterment of all.

I tried to ask if she thought differently when speaking in the different languages, but she seemed to have some trouble understanding what I was getting at. I think I got the point across eventually, but she only gave a vague 'not really' and didn't seem to think there was a difference. Not being able to speak Vietnamese myself, I was unable to check.

Linguistic Families

Given that English is an Indo-European language and Vietnamese is an Austro-Asiatic language, there is almost no relation between the two whatsoever.

Realistically speaking, I know that the Colonial French merely conquered Vietnam and, as they usually did, simply tried to replace it. However, I do know that the Chinese and English did develop a trading pidgin language in the 17th century, and I suspect the process would have been similar in Vietnam.

Given their relative positions at the time period, English would have been the dominant form, and its lexicon would have been used over Vietnamese grammar, much as it did with the Chinese.

Realistically speaking, I know that the Colonial French merely conquered Vietnam and, as they usually did, simply tried to replace it. However, I do know that the Chinese and English did develop a trading pidgin language in the 17th century, and I suspect the process would have been similar in Vietnam.

Given their relative positions at the time period, English would have been the dominant form, and its lexicon would have been used over Vietnamese grammar, much as it did with the Chinese.

Language Play and Acquisition

There is a language game called NOI LAI that she knows about, though she said she rarely did it herself. It consists of switching the tones of two words and their order (or that of their first consonants.) For example:

Chu-ah hong -> ho-ang chu-ah

Unmarried pregnancy -> Are you scared?

She had a deal more to say about language acquisition and the treatment of children. Children are, evidently, much cared for in Vietnamese society; when the child shows the slightest distress, the parents will be there in a moment to find out what's wrong. When speaking to a child, a soft voice and simple words are used. Children are generally expected to keep quiet, especially in social settings. Teachers are supposed to be respected in similar fashion.

My partner seemed to find this rather restraining, noting that a girl-child is not considered an adult until married, even though by law it's when she's 18. Indeed, Vietnamese parents tend to be preoccupied with their children even after this point. Typically, Vietnamese get married in their 20s (counting women, so it seems they don't get married at a much younger age than the men.) They will have 2 or so children on average and will frequently find work with the help of their family contacts.

I found it interesting that she was somewhat disdainful of this system, she seemed very enamored of the American equivalents.

Chu-ah hong -> ho-ang chu-ah

Unmarried pregnancy -> Are you scared?

She had a deal more to say about language acquisition and the treatment of children. Children are, evidently, much cared for in Vietnamese society; when the child shows the slightest distress, the parents will be there in a moment to find out what's wrong. When speaking to a child, a soft voice and simple words are used. Children are generally expected to keep quiet, especially in social settings. Teachers are supposed to be respected in similar fashion.

My partner seemed to find this rather restraining, noting that a girl-child is not considered an adult until married, even though by law it's when she's 18. Indeed, Vietnamese parents tend to be preoccupied with their children even after this point. Typically, Vietnamese get married in their 20s (counting women, so it seems they don't get married at a much younger age than the men.) They will have 2 or so children on average and will frequently find work with the help of their family contacts.

I found it interesting that she was somewhat disdainful of this system, she seemed very enamored of the American equivalents.

Proxemics and Kinesics

Though she did not feel she could speak for Vietnamese as a whole (for the most part) I was able to get some information.

Interestingly, I found that when it comes to personal space, they are very similar to ourselves, though in a more pronounced way. Strangers are considered exceedingly unwelcome in a Vietnamese person's space, and she feels very uncomfortable standing anywhere near someone she doesn't know. When it comes to people she does know, however, especially family, the distance of comfort narrows to 0-3 inches. This dichotomy of 'stranger' and 'known' seems to be significantly more important than the four zones.

Interestingly, women prefer to keep more space than men do (particularly between themselves and men) while men actually prefer to stand very close to each other, something of the opposite of what we find here in the United States.

She also added that women tend to prefer to socialize and spend time in the kitchen and related areas and men in other areas of the house (particularly if there's a TV) but these are by no means formal or necessary differences, merely preferential and habitual.

Rather like the United States, a nod of the head means 'I agree.' Whether this is a colonial influence or historic, neither of us were sure. Avoiding eye contact is a way of showing respect towards the elderly or those higher in status, and bowing is a greeting and a way of showing great respect to anyone.

One she showed me was when she held her palm out, and wriggled her fingers; this is to tell someone to 'come here' and is not used with people higher in the pecking order.

A middle finger crossing over a forefinger (with the other fingers closed) is considered obscene, something she described rather than demonstrated.

Interestingly, I found that when it comes to personal space, they are very similar to ourselves, though in a more pronounced way. Strangers are considered exceedingly unwelcome in a Vietnamese person's space, and she feels very uncomfortable standing anywhere near someone she doesn't know. When it comes to people she does know, however, especially family, the distance of comfort narrows to 0-3 inches. This dichotomy of 'stranger' and 'known' seems to be significantly more important than the four zones.

Interestingly, women prefer to keep more space than men do (particularly between themselves and men) while men actually prefer to stand very close to each other, something of the opposite of what we find here in the United States.

She also added that women tend to prefer to socialize and spend time in the kitchen and related areas and men in other areas of the house (particularly if there's a TV) but these are by no means formal or necessary differences, merely preferential and habitual.

Rather like the United States, a nod of the head means 'I agree.' Whether this is a colonial influence or historic, neither of us were sure. Avoiding eye contact is a way of showing respect towards the elderly or those higher in status, and bowing is a greeting and a way of showing great respect to anyone.

One she showed me was when she held her palm out, and wriggled her fingers; this is to tell someone to 'come here' and is not used with people higher in the pecking order.

A middle finger crossing over a forefinger (with the other fingers closed) is considered obscene, something she described rather than demonstrated.

Sentence Structure

English is, as we know, a Subject-Verb-Object language, rather unlike Persian, which is Subject-Object-Verb. Vietnamese is, like Persian, usually Subject-Object-Verb.

Ban taen gi?

You name what?

Subject-Object-Verb

However, it gets a bit strange after that. Note the sentence below, which is Subject-Verb-Object instead, rather like English.

Toi noi du-doc (ti-eng Ang).

I speak can English.

Subject-Verb-Verb-Object.

And an especially strange sentence she gave me. I needed to work it out in my head a bit to get it.

Du-doc fep chay ki den xhan.

Have right drive when light green.

Verb-Object-Object-Adverb-Object-Adjective.

You have the right to drive when the light is green.

You may also add "kong?" to the end of the sentence, it becomes a question of whether you can or not, confusing the syntax further.

Moving on to negatives, we start with a simple sentence, with the same structure as the first one presented.

Toy sahng oh Sai-gon.

I live at Saigon.

The negative form of this sentence (I don't live in Saigon) would be:

Toi kong sahng oh Sai-gon.

I not live at Saigon.

Subject-Adverb-Verb-Prep-Object

Almost exactly how it would be said in English, in terms of syntax. The interrogative form (of a second person version) demonstrates a bit of a difference.

Ban sang o Sai-gon fy kong?

You live at Saigon should not?

Subject-Verb-Prep-Object-Verb-Verb?

Though a little peculiar to an English speaker, this is asking whether or not the person being spoken to lives in Saigon.

Though initially similar, Vietnamese syntax confuses me with some of the twists it takes, and my partner was unable to explain the difference why herself. I can imagine any number of syntactic mistakes an English person might make in Vietnamese, though my partner suggests that the person should still be comprehensible, though native speakers might be amused at how odd it sounds. From Vietnamese to English, I can see a few obvious examples; asking if I 'live in Mission Viejo should not?' would certainly sound odd, but, on the other hand, 'You live in Mission Viejo, no?' would be used by native English speakers. Asking 'have right drive when light green, no?' might require a few reiterations to get the point across.

Ban taen gi?

You name what?

Subject-Object-Verb

However, it gets a bit strange after that. Note the sentence below, which is Subject-Verb-Object instead, rather like English.

Toi noi du-doc (ti-eng Ang).

I speak can English.

Subject-Verb-Verb-Object.

And an especially strange sentence she gave me. I needed to work it out in my head a bit to get it.

Du-doc fep chay ki den xhan.

Have right drive when light green.

Verb-Object-Object-Adverb-Object-Adjective.

You have the right to drive when the light is green.

You may also add "kong?" to the end of the sentence, it becomes a question of whether you can or not, confusing the syntax further.

Moving on to negatives, we start with a simple sentence, with the same structure as the first one presented.

Toy sahng oh Sai-gon.

I live at Saigon.

The negative form of this sentence (I don't live in Saigon) would be:

Toi kong sahng oh Sai-gon.

I not live at Saigon.

Subject-Adverb-Verb-Prep-Object

Almost exactly how it would be said in English, in terms of syntax. The interrogative form (of a second person version) demonstrates a bit of a difference.

Ban sang o Sai-gon fy kong?

You live at Saigon should not?

Subject-Verb-Prep-Object-Verb-Verb?

Though a little peculiar to an English speaker, this is asking whether or not the person being spoken to lives in Saigon.

Though initially similar, Vietnamese syntax confuses me with some of the twists it takes, and my partner was unable to explain the difference why herself. I can imagine any number of syntactic mistakes an English person might make in Vietnamese, though my partner suggests that the person should still be comprehensible, though native speakers might be amused at how odd it sounds. From Vietnamese to English, I can see a few obvious examples; asking if I 'live in Mission Viejo should not?' would certainly sound odd, but, on the other hand, 'You live in Mission Viejo, no?' would be used by native English speakers. Asking 'have right drive when light green, no?' might require a few reiterations to get the point across.

Friday, May 16, 2008

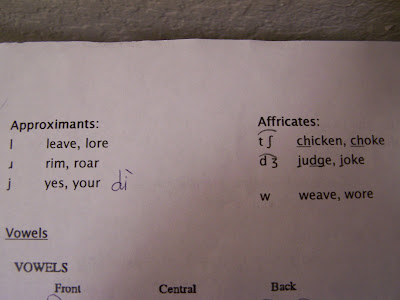

Phonology

Of all the assignments, this one was the most difficult and the most frustrating, for both of us. Even practicing, I had a great deal of difficulty pronouncing some of the letters for her to hear, and even then had to repeat fairly often. I did, however, eventually manage to confirm all the sounds noted on the GMU website.

I tried to find a few more, but she was getting rather frustrated. I went back to it another day, but also failed to find any more sounds, for which she apologized. I let her know there was no need to apologize (even aside from her having no stake in this, unlike me.) She wasn't exactly a Vietnamese teacher, and I have trouble enough finding my own language's phonemes.

(Correction: Looking at my notes again I found the Bilabial Plosive phoneme /p/. This has been added to the chart below. All of the others I found merely confirmed what the chart had.)

Like many languages, I noted that Vietnamese distinctly lacked a 'th' sound, though she had learned how to pronounce it properly. English is, in fact, taught in many Vietnamese schools, but that's for a later assignment. Vietnamese is surprisingly easy to pronounce for the most part; included below are some samples. The words blanked out are her name.

I tried to find a few more, but she was getting rather frustrated. I went back to it another day, but also failed to find any more sounds, for which she apologized. I let her know there was no need to apologize (even aside from her having no stake in this, unlike me.) She wasn't exactly a Vietnamese teacher, and I have trouble enough finding my own language's phonemes.

(Correction: Looking at my notes again I found the Bilabial Plosive phoneme /p/. This has been added to the chart below. All of the others I found merely confirmed what the chart had.)

Like many languages, I noted that Vietnamese distinctly lacked a 'th' sound, though she had learned how to pronounce it properly. English is, in fact, taught in many Vietnamese schools, but that's for a later assignment. Vietnamese is surprisingly easy to pronounce for the most part; included below are some samples. The words blanked out are her name.

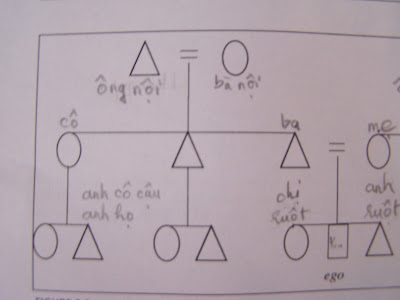

Kinship

We've switched to doing these on Fridays. Evidently she had some trouble getting to her bus after the Wednesday meetings.

Regardless, we moved on with my next assignment, Kinship patterns. This time, she seemed to get what I was asking pretty quickly.

This first image traces the patricial side.

This second image is the matrilineal side.

This second image is the matrilineal side.

As seen, there are a few differences between each. A paternal Grandfather is a ONG NOI, while a maternal Grandfather is a ONG NGOAI (pardon the lack of diacritics.) These terms extend into aunts, uncles, and cousins of various sorts. For a native English speaker with no experience in other languages, this may be a bit confusing. I had already been exposed to this possibility in German (der cousin, die cousine,) when it comes to differences between male and female cousins, but no distinction is made in terms of descent. Sadly, she did not know why this is so.

Looking around online, I found that kinship terms are often used as honorifics.

No questions about Vietnam here, aside from about kinship.

Regardless, we moved on with my next assignment, Kinship patterns. This time, she seemed to get what I was asking pretty quickly.

This first image traces the patricial side.

This second image is the matrilineal side.

This second image is the matrilineal side.

As seen, there are a few differences between each. A paternal Grandfather is a ONG NOI, while a maternal Grandfather is a ONG NGOAI (pardon the lack of diacritics.) These terms extend into aunts, uncles, and cousins of various sorts. For a native English speaker with no experience in other languages, this may be a bit confusing. I had already been exposed to this possibility in German (der cousin, die cousine,) when it comes to differences between male and female cousins, but no distinction is made in terms of descent. Sadly, she did not know why this is so.

Looking around online, I found that kinship terms are often used as honorifics.

No questions about Vietnam here, aside from about kinship.

Wednesday, May 7, 2008

Color Chart

I met my conversation partner, a young woman who came here from Vietnam just a month or two before the semester began, in the grungy cafeteria of our dear Saddleback College. Perhaps not the most comfortable setting, but servicable and offering few distractions to the task at hand.

She was, perhaps, a year or two older than I and quite a bit shorter. Her grasp of English was actually quite firm (as it turns out, English is a very common second language in Vietnam,) though I, at times, had trouble with her accent and had to ask her to repeat herself now and then.

We settled down this particular day to talk about color perception.

Curiously, I had some trouble in getting her to understand the assignment, but, eventually, she was assured that she wasn't being graded and that she could make definitions wherever she pleased.

As seen here, our color charts are remarkably similar. Remarkable largely due to my color-blindeness. Indeed, I suspect the similarities to be otherwise expected, as the Vietnamese people had been under Western colonial rule for a considerable amount of time. They even changed their language from a pictographic one to one with words in the Latin alphabet with a large number of diacritics to distinguish letters.

As seen here, our color charts are remarkably similar. Remarkable largely due to my color-blindeness. Indeed, I suspect the similarities to be otherwise expected, as the Vietnamese people had been under Western colonial rule for a considerable amount of time. They even changed their language from a pictographic one to one with words in the Latin alphabet with a large number of diacritics to distinguish letters.

In addition to following the listed assignment, I also took the liberty of asking a few questions of my own about her culture and her country, owing to a particular interest in Vietnam. My partner, who I shall not name in these pages, was born in a small town near Saigon called Tien Giang, and she came to the United States for study purposes. She first learned English in the Sixth grade, a key subject in Vietnamese schools. She currently lives with her aunt and uncle, the latter of whom - a veteren of ARVN, or the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, who fought for the South - I asked more questions about in a later piece.

She was, perhaps, a year or two older than I and quite a bit shorter. Her grasp of English was actually quite firm (as it turns out, English is a very common second language in Vietnam,) though I, at times, had trouble with her accent and had to ask her to repeat herself now and then.

We settled down this particular day to talk about color perception.

Curiously, I had some trouble in getting her to understand the assignment, but, eventually, she was assured that she wasn't being graded and that she could make definitions wherever she pleased.

As seen here, our color charts are remarkably similar. Remarkable largely due to my color-blindeness. Indeed, I suspect the similarities to be otherwise expected, as the Vietnamese people had been under Western colonial rule for a considerable amount of time. They even changed their language from a pictographic one to one with words in the Latin alphabet with a large number of diacritics to distinguish letters.

As seen here, our color charts are remarkably similar. Remarkable largely due to my color-blindeness. Indeed, I suspect the similarities to be otherwise expected, as the Vietnamese people had been under Western colonial rule for a considerable amount of time. They even changed their language from a pictographic one to one with words in the Latin alphabet with a large number of diacritics to distinguish letters.In addition to following the listed assignment, I also took the liberty of asking a few questions of my own about her culture and her country, owing to a particular interest in Vietnam. My partner, who I shall not name in these pages, was born in a small town near Saigon called Tien Giang, and she came to the United States for study purposes. She first learned English in the Sixth grade, a key subject in Vietnamese schools. She currently lives with her aunt and uncle, the latter of whom - a veteren of ARVN, or the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, who fought for the South - I asked more questions about in a later piece.

Late Start!

I've waited far too long to start putting these up, I'll admit. I've never been much of a blogger and the idea of doing it for the first time with a class was rather intimidating.

No matter, here they come! Updates will be fast-paced and frequent, I should hope.

No matter, here they come! Updates will be fast-paced and frequent, I should hope.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)